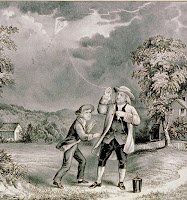

So frequently repeated are the story of Franklin flying a kite in the lightning storm and the title of Poor Richard's Almanack that we rarely get a chance to learn about the other contributions of Franklin. (Whose face and build are also widely recognized from the many portraits of him, some with the illumination of a lightning strike.). Some people in the general public might know a bit about his having lived in France for awhile as part of his public service for his countrymen back in America. Or maybe know about his fiddling with science even beyond that kite. But we hear little about his religious habits or his spirituality.

So frequently repeated are the story of Franklin flying a kite in the lightning storm and the title of Poor Richard's Almanack that we rarely get a chance to learn about the other contributions of Franklin. (Whose face and build are also widely recognized from the many portraits of him, some with the illumination of a lightning strike.). Some people in the general public might know a bit about his having lived in France for awhile as part of his public service for his countrymen back in America. Or maybe know about his fiddling with science even beyond that kite. But we hear little about his religious habits or his spirituality.That omission is why I was struck by one page in the book Gentlemen Scientists and Revolutionaries: The Founding Fathers in the Age of Enlightenment by Tom Shachtman. That author emphasizes that:

"The Founding Fathers' science was in no way opposite to their religion.

The notion that science and religion were antithetical

is a nineteenth-century construct."

And in regard to Franklin, Shachtman writes:The notion that science and religion were antithetical

is a nineteenth-century construct."

"By the age of fifteen, Franklin wrote in his Autobiography, he had become

a doubter of organized religion...until he chanced upon printed lectures that

tried to debunk Deism: [Franklin wrote:] ' They wrought an effect on me quite contrary

to what was intended by them, for the arguments of the Deists...appeared to me

much stronger than the refutations; in short I soon became a thorough Deist.'

In his twenties, he set out his religious beliefs

in a ten-page liturgy, complete with a hymn."

Benjamin Franklin's explanation of his newly found religious orientation continues:a doubter of organized religion...until he chanced upon printed lectures that

tried to debunk Deism: [Franklin wrote:] ' They wrought an effect on me quite contrary

to what was intended by them, for the arguments of the Deists...appeared to me

much stronger than the refutations; in short I soon became a thorough Deist.'

In his twenties, he set out his religious beliefs

in a ten-page liturgy, complete with a hymn."

"I think it seems required of me, and my Duty, as a Man,

to pay Divine Regards to SOMETHING....

When I stretch my Imagination thro' and beyond...the visible fix'd Stars themselves,

into that Space that is every Way infinite, and conceive it fill'd with Suns like ours...,

then this little Ball on which we move, seems, even in my narrow Imagination,

to be almost Nothing, and my self less than nothing."

to pay Divine Regards to SOMETHING....

When I stretch my Imagination thro' and beyond...the visible fix'd Stars themselves,

into that Space that is every Way infinite, and conceive it fill'd with Suns like ours...,

then this little Ball on which we move, seems, even in my narrow Imagination,

to be almost Nothing, and my self less than nothing."

The second thing I liked was Franklin's expression of his need to feel reverence (the paying of "Divine Regards," as he interestingly put it). Our media today are so quickly drawn towards brash voices and dominating personalities that it is easy to forget that we are often better served by humility. And in religious and spiritual lives, humility is cultivated through following a path of reverence.

~ ~ ~

How do you think we can find a good midpoint between the extremes of brashness and timidity?

(Quotations are taken from Shachtman's Gentlemen Scientists and Revolutionaries, © 2014, pp. xii-xiv.)

(Both pictures are details from the originals, both of which are in the public domain.)

(Both pictures are details from the originals, both of which are in the public domain.)