One luxury of our modern Western societies is that many of us are able to have a plenitude of Christmas decorations. The selections in Christmas stories reveal the enduring popularity of nativity scenes, from folk pottery of South America to wood carvings of Asia. My wife says that as a child her favorites were nativity scenes that allowed her to move unattached figures about. And, of course, some of the favorites of children in those scenes are, understandably, the animals.

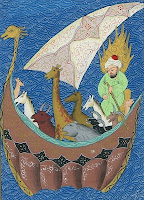

Seeing a child play with those animals that are a part of Jesus's birth-scene often makes me think of a similar children's toy: the arks with pairs of animals, based on the story of the flood in the Bible's book of Genesis. (Christianity shares with Judaism that version of the story of animals being saved; and the figure of Noah as rescuer is also in Islam's Qur'an.) Young children enjoy animating the animals by moving them about. And figuring out how to fit all the animals into the ark can be a learning experience.

Our contemporary dictionaries have several definitions for "ark," but one older use of the word endures only in history-recording dictionaries such as the Oxford English. In the 1700's and 1800's, English gentlemen (and their counterparts in U.S.'s New England) were often collectors of objects from nature: fossils, plant samples, bones, insects, etc. If the collector could afford it, he kept those samples in a multi-drawered cabinet that came to be called an "ark." The Biblical connection was so strong that the wood cabinets were sometimes even designed with a sloping top -- the way the roof of Noah's ark would have to have been sloped so the rain would run off.

Natural scientists of that time period had a "fitting" problem that was even greater than how to fit their growing number of samples into their arks (and even more challenging than children getting toy animals back into their ark). Namely, figuring out how all the fossils, plants, and animals represented by their samples fit together historically and biologically. Eventually, Darwin's discovery would prove to be a breakthrough.

This story of the resourcefulness of natural science converges with the resourcefulness of Christianity with its nativity scenes. That is because the Bible itself does not explicitly depict any animals surrounding baby Jesus in the manger. Sheep are only referred to indirectly in the Bible's book of Luke; camels are never mentioned in the story of the magi in Matthew; and no donkey is mentioned. All those animals around the Christmas manger are thus the product of humans' imaginatively interpreting the meaning of the Biblical stories. It seems as if representing the glory of new creation and the glory of God demanded a more holistic picture -- one that involved a range of animals.

Today, for some of us, another dimension -- another aura -- surrounds those nativity scenes. Just like Noah, we humans today are trying to rescue animals from extinction by trying to evoke in our human hearts a new birth of the spirit of Creation-Care. On this ark of planet Earth.

Today, for some of us, another dimension -- another aura -- surrounds those nativity scenes. Just like Noah, we humans today are trying to rescue animals from extinction by trying to evoke in our human hearts a new birth of the spirit of Creation-Care. On this ark of planet Earth.

~~~

Do you have any childhood memories involving crèches or living nativity scenes?

(The picture of a nativity is used under a

Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license by L.Kenzel.

Both illustrations of Noah are in the public domain because their copyrights have expired.)

Both illustrations of Noah are in the public domain because their copyrights have expired.)

.jpg)