Paris's second largest church building, the much less famous Church of Saint-Sulpice, has had an interesting intersection with a novel, but in a quite different way. And that intersection may say something about our human struggles to bring the illumination of both science and religion to our world.

Now on display in Saint-Sulpice is this note about the long, straight line in the 17th-century church's floor:

"Contrary to fanciful allegations in a recent best-selling novel,

this [line] is not a vestige of a pagan temple.

No such temple ever existed in this place.

It was never called a "Rose-Line'."

The "best-selling novel" discreetly referred to is the 2003 book The Da Vinci Code by Dan Brown.this [line] is not a vestige of a pagan temple.

No such temple ever existed in this place.

It was never called a "Rose-Line'."

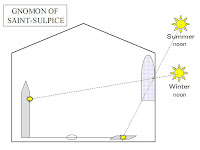

The inlaid brass line is in fact part of a device (a "gnomon") for knowing when the spring equinox occurs, based on where during the course of a year a noon-time shaft of light falls along that line, or on the obelisk at the far end of it. The word "gnomon" has its root in the Greek word for "to know." But there is much that Brown does not appear to know (or desire to convey) about the true history of this gnomon. The religious reason for discerning the spring equinox is explained by an inscription on the obelisk's base: "Ad Certam Paschalis," or "for the determination of Easter." That religious task, as the 20th-century scientist Stephen Jay Gould explained, "requires considerable astronomical sophistication, for lunar and seasonal cycles must both be known with precision."

The inlaid brass line is in fact part of a device (a "gnomon") for knowing when the spring equinox occurs, based on where during the course of a year a noon-time shaft of light falls along that line, or on the obelisk at the far end of it. The word "gnomon" has its root in the Greek word for "to know." But there is much that Brown does not appear to know (or desire to convey) about the true history of this gnomon. The religious reason for discerning the spring equinox is explained by an inscription on the obelisk's base: "Ad Certam Paschalis," or "for the determination of Easter." That religious task, as the 20th-century scientist Stephen Jay Gould explained, "requires considerable astronomical sophistication, for lunar and seasonal cycles must both be known with precision."The sun-calculating device in the Church of Saint-Sulpice is not an exotic oddity, as one might think reading Brown's book. In fact, other similar installations (sometimes called "meridian lines") can be found in cathedrals in Rome, Florence, and Bologna, Italy -- all demonstrating conjunctions of the Church and astronomy. Even beyond those other installations, there is additional evidence that Saint-Sulpice's gnomon has real Christian roots, and is not a pagan import: The Christian practice of scientifically calculating solar equinoxes was mastered notably by an English monk living in the 700's, the Venerable Bede. He developed tables for calculating Easter for the three centuries yet to come. His manual for that scientific field called "computus" continued to be used into the Middle Ages.

And what about the letters "P" and "S" in two of Saint-Sulpice's windows? Here again, the notice posted in the cathedral brings illumination:

"Please also note that the letters "P" and "S" in the small round windows

at both ends of the transept refer to Peter and Sulpice, the patron saints of the church,

and not an imaginary "Priory of Sion" [a secret society in Brown's novel ]."

at both ends of the transept refer to Peter and Sulpice, the patron saints of the church,

and not an imaginary "Priory of Sion" [a secret society in Brown's novel ]."

The architecture of the Church of Saint-Sulpice is not to my personal taste. Nevertheless, I can admire the openness not only of the people who built Saint-Sulpice, but also the other Christian minds stretching back to the Venerable Bede and even beyond -- bringing together knowledge and inspiration from both science and religion.

~ ~ ~

(The quotation by Stephen Jay Gould is from his Dinosaur in a Haystack, © 1995, p. 39.)